About the Author: Rohit Jayakar MD specializes in non-surgical Sports Medicine (Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation). He treats a variety of musculoskeletal injuries, neurological injuries, and pain conditions.

What can you do to prevent low back pain?

An individualized and consistent approach is necessary in order to have the best chance of reducing low back pain, especially for chronic cases (>3 months). Restoring hip, spine, and shoulder mobility, breaking abnormal movement patterns, focusing on left and right asymmetries in mobility and weakness, strengthening the core (this includes the very important glutes!), and activating appropriate muscle groups at the right time (neuromuscular control) are all critical. I will break my recommendations down by categories: Mobility, Biomechanics, and Core Strengthening.

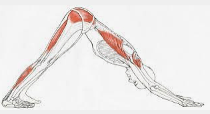

Mobility: Those with poor spine and hip mobility are at a higher risk of low back injuries, from muscle strains to herniated discs. What often gets missed is how the hips affect the spine. If the hips are very stiff, more motion is required from the spine while playing. Yoga can be a great way to add flexibility while simultaneously building balance, stability, and core strength. In addition, here are some specific stretches that are a good addition for daily hip and spine mobility exercises. Try and notice asymmetries while you are performing these and consider focusing more time on the side with more restriction.

- Hips

- Spine

Posture and Biomechanics:

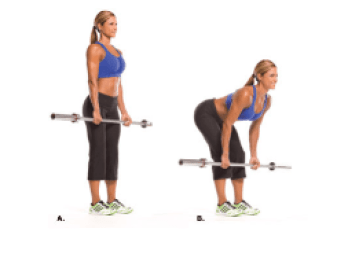

Hip Hinging: As mentioned above, a biomechanically sound hip hinge is crucial to prevent increased pressure on the spine. The key to a proper hip hinge is to focus on pulling the hips posteriorly (backwards), as opposed to bending forward with the back. This primarily uses the glutes and hamstrings rather than the back. Note that a hip hinge is not the same as a squat, which is primarily driven by knee flexion rather than hip flexion. In a squat, your hips are moving downwards, whereas in a hip hinge, they are moving backwards. Here are some tips on the hip hinge maneuver:

I. Makes sure to maintain a neutral spine. Do not bend the low back.

II. Squeeze the glutes

III. Imagine being pulled by a string directly backwards from your tailbone. This cue helps the initiation of the movement from your hips rather than the spine.

This is not easy. A good way to practice this is hold a rod vertically behind your back. The rod should contact your head, middle of your spine (thoracic spine), and sacrum (bottom of your spine) while you are hip hinging. Make sure your chest is open and shoulder blades are squeezed together as well. You should not have variability in the curve of your spine during this movement. Here is an example:

Once the above is mastered, you can move on to doing weighted hinges, but only if you are able to keep the correct form:

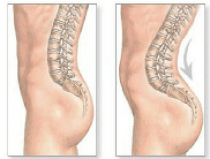

Pelvic tilt: Pelvic tilt is determined by the muscle balance between the hip flexors and hip extensors. The hip flexors include the iliopsoas muscles (iliacus, psoas major, psoas minor) and rectus femoris (one of the quadriceps muscles), while the hip extensors include primarily the gluteus maximus and hamstrings. Anterior pelvic tilt is much more common than posterior pelvic tilt – a sedentary lifestyle or prolonged sitting often causes the hip flexors to become tight and shortened. On top of that, in those with weak glutes and hamstrings, this causes the pelvis to tilt even more anteriorly (forward). When the pelvis is shifted in this way, it exaggerates the normal curve in the low back (termed hyperlordosis), which increases stress on the back muscles and increases the risk of injury. I’ll discuss how to prevent this in the strengthening section, but here are some examples of anterior pelvic tilt:

Core Strengthening:

Strengthening is one of the most important pieces in preventing low back injuries and reducing anterior pelvic tilt. Some form of core strengthening should be done at least 3-4 days a week, but daily is even better. In those who already have a regular core exercise program, the main problem I see is that they often focus on just the abdominal muscles and neglect the hip extensors, obliques, and paraspinals. This may produce muscle imbalances and can even exacerbate pelvic tilt issues. Dr. Stuart McGill, a renowned expert and educator on spine injury prevention and rehabilitation, recommends “The Big 3” exercises for spine stability. If you want an additional in-depth reading, I recommend his book The Back Mechanic. The Big 3 will be specifically called out (**) in my list of recommended exercises below to get started on a balanced core routine.

Abdominal Muscles and Hip Flexors

Plank: This may seem like a straightforward exercise, but as with all of these exercises, it is important to have good form. The spine should be neutral and the pelvis should not sag, which causes the spine to hyperextend. Similarly, if the hips are too high, the exercise will not be as effective.

Deadbug: Alternate one hand and one leg (can be opposite leg or the same leg, both variations are good), and bring back to meet the other arm and leg. Note that with most supine (lying on your back) abdominal exercises, the key is to make sure the low back does not lift off the ground. This not only places a lot of stress on the back but also causes ineffective activation of the abdominals.

Curl up** (McGill Big 3): Place the hands under your low back for support. One leg is straight, and one is bent. Crunch up and hold briefly. This is a subtle movement and should only be done in the accessible range of motion. The neck should remain in a relatively neutral position. The neck should not be flexing so much that the chin is getting close to the chest,

There are no shortage of abdominal and hip flexor exercises if you want more variety in your routine. I won’t get into all of these, but just to name a few: Flutter kicks, crunches, leg raises, reverse crunches, bicycles, Russian twists, and sprinter situps are all good additions.

Oblique Muscles

Side plank** (McGill Big 3): In addition to traditional side plank, I am a big fan of side plank variations (dips, leg raise, thoracic spine rotations) for more of a challenge. The leg raise variation will add some tough glute work on both sides. For those who need a modification, side plank on knees is a good alternative.

Hip extensors (glutes, hamstrings) and Paraspinals: these are generally the most neglected of the core muscles, but arguably the most important. They help fight anterior pelvic tilt and offload the spine.

Bird Dogs** (McGill Big 3): The bird dog is one of the best exercises on the list. It simultaneously strengthens the glutes, hamstrings, and paraspinals while also activating the abdominal muscles. The opposite arm and leg should be extended, and the low back should not be curving while extending the leg. The pelvis should be stabilized, and not rocking from side to side during the exercise. For an additional challenge, add ankle weights!

Glute Bridge: This can be done as a static movement or while thrusting the pelvis upwards and not allowing the knees to collapse inwards. Emphasis should be placed on glute activation. For an additional challenge, hold a weight on your pelvis and/or a band above the knees to focus more on hip abduction.

Monster Walks: Use a band above the knees and step laterally in each direction with the knees at a comfortable bend. Move the band to the ankles to make it more difficult.

Hip Abduction: This can be done lying on the side with straight legs, or with bent knees (clamshell variation). With the straight leg version, the lower the band the more challenging it will be.

General Exercise Tips:

The CDC recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity (e.g. brisk walking) or 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity (e.g. running) per week, in addition to 2 days a week of muscle strengthening. Exercise not only improves muscular and cardiovascular health, but also helps with stress, mood, sleep, and the management of chronic conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes.

In my opinion, the CDC guidelines are not nearly sufficient and should be viewed as the bare minimum. I recommend at least 1 hour of physical activity per day. Some form of cardiovascular activity should be done daily (eg. walking, running, swimming, HIIT, or other sports), and strengthening should be done at least 3-4 times per week. Strengthening can take many forms: Weight training, body weight exercises, banded resistance training, machines, yoga, and of course the core strengthening above. Cross training and variety in your exercise program are important to keep your body optimal (i.e., not doing the same thing every day). Lastly, you should listen to your body and in general it is usually not a good idea to push through any significant pain, as doing so may exacerbate the injury.

When do you need to see a physician?

Low back pain is one of the most common complaints during a primary care visit, and most people will have at least one episode of significant low back pain in their lives. The good news is that most causes of low back pain are benign and not due to a serious medical problem. Low back pain can generally be broken down into 3 main categories:

Nonspecific low back pain

- This is the most common and involves deep muscles, chronic muscular strains/imbalances, and/or ligamentous strains.

Osteoarthritic pain/ Degenerative disc disease

- Most people will have some degree of age-related bony changes (osteoarthritis) seen on MRI starting in their 20s and 30s. It is better to think of these changes similar to wrinkles on the skin, and often these changes do not cause any problem unless the surrounding structures (ie. muscles) aren’t working like they should. These “wrinkles” or arthritic changes can become symptomatic without their surrounding protection and can become a contributor to pain with movement. To read more about how to preserve bone health and healthy aging, read my article here.

Discogenic and radicular pain

- Herniated discs, bulging out of the cushions between the vertebral bodies (ie. bones), can occur and impinge on the nerve roots that leave the spine and go down the legs. This is called radiculopathy or colloquially “sciatica.” Symptoms may include numbness, tingling, or weakness in the legs.

In general, you should be seeing a physician if:

- Symptoms have been going on > 4 weeks with no major improvement

- The pain is significantly interfering with your life or preventing you from doing the activities you enjoy

- Symptoms are going down your leg(s), such as numbness, tingling, pain, or weakness

- You have fevers, chills, or nightsweats

- You have new or worsening pain and a history of back surgery

This list is not exhaustive, but certainly these are indications to see a provider for a detailed neurological exam and to determine if imaging (likely MRI) or additional testing is indicated, as well as to get treatment for the symptoms.

I hope the strategies in this article help you stay out on the court longer and reach your fitness goals. If they don’t seem to be working for you, remember that regaining mobility, adjusting your biomechanics, and building strength take time. Often, you need a more detailed evaluation to identify and treat your specific condition, as well as formal physical therapy sessions for a more focused and individualized approach.

Rohit Jayakar, MD

References and Additional Resources:

Callaghan, J.P., and McGill, S.M. (2001) Intervertebral disc herniation: Studies on a porcine model exposed to highly repetitive flexion/extension motion with compressive force. Clin. Biom. 16(1): 28‐37.

Childs, J.D., George, S.Z., Wright, A., Dugan, J.L., Benedict, T., Bush, J., Fortenberry, A., Preston, J., McQueen, R., Teyhen, D.S., (2009) The effects of traditional sit‐up training versus core stabilization exercises on sit‐up performance in US Army Soldiers: A cluster randomized trial, J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., 39(1): A18.

D’Ambrosia, P., King, K., Davidson, B., Zhou, B., Lu, Y., Solomonow, M., (2010) Pro‐inflammatory cytokines expression increases following low and high magnitude cyclic loading of lumbar ligaments, Eur. Spine J., doi 10.1007/s00586‐010‐1371‐4.

Ikeda, D., McGill, S.M. (2012) Can altering motions, postures and loads provide immediate low back pain relief: A study of four cases investigating spine load, posture and stability. SPINE. 37 (23): E1469‐E1475 Lee, B., and McGill, S.M., (in press) The “Big 3” stabilization exercises enhance spine stiffness.

McGill, S.M. Invited Paper. (1998) Low back exercises: Evidence for improving exercise regimens. Physical Therapy 78(7): 754‐765.

McGill, S.M. Ultimate back fitness and performance, Backfitpro Inc., Waterloo, Canada, ISBN 0‐ 9736018‐0‐4 (www.backfitpro.com). Fifth edition 2014.

Scannell, J.P., McGill, S.M. (2009) Disc prolapse: Evidence of reversal with repeated extension. SPINE, 34(4): 344‐350.

Snook, S.H., Webster, B.S., McGarry, R.W., Fogleman, D.T., McCann, K.B., (1998) The reduction of chronic non‐specific low back pain through the control of early morning lumbar flexion: A randomized controlled trial, SPINE, 23(23):2601‐2607.

Tampier, C., Drake, J., Callaghan, J., McGill, S.M. (2007) Progressive disc herniation: An investigation of the mechanism using radiologic, histochemical and microscopic dissection techniques. SPINE, 32(25): 2869‐2874.

Veres, S.P., Robertson, P.A., Broom, N.D., (2009) The morphology of acute disc herniation: A clinically relevant model defining the role of flexion. SPINE: 34(21):2288‐2296.

Yates, J.P., Giangregorio, L. and McGill, S.M. (2010) The influence of intervertebral disc shape on the pathway of posterior/posterior lateral partial herniation. SPINE. 35 (7):734‐739.

Yingling, V.R., Callaghan, J.P., and McGill, S.M. (1999) The porcine cervical spine as a reasonable model of the human lumbar spine: An anatomical, geometrical and functional comparison. J. Spinal Disorders 12(5): 415‐423.